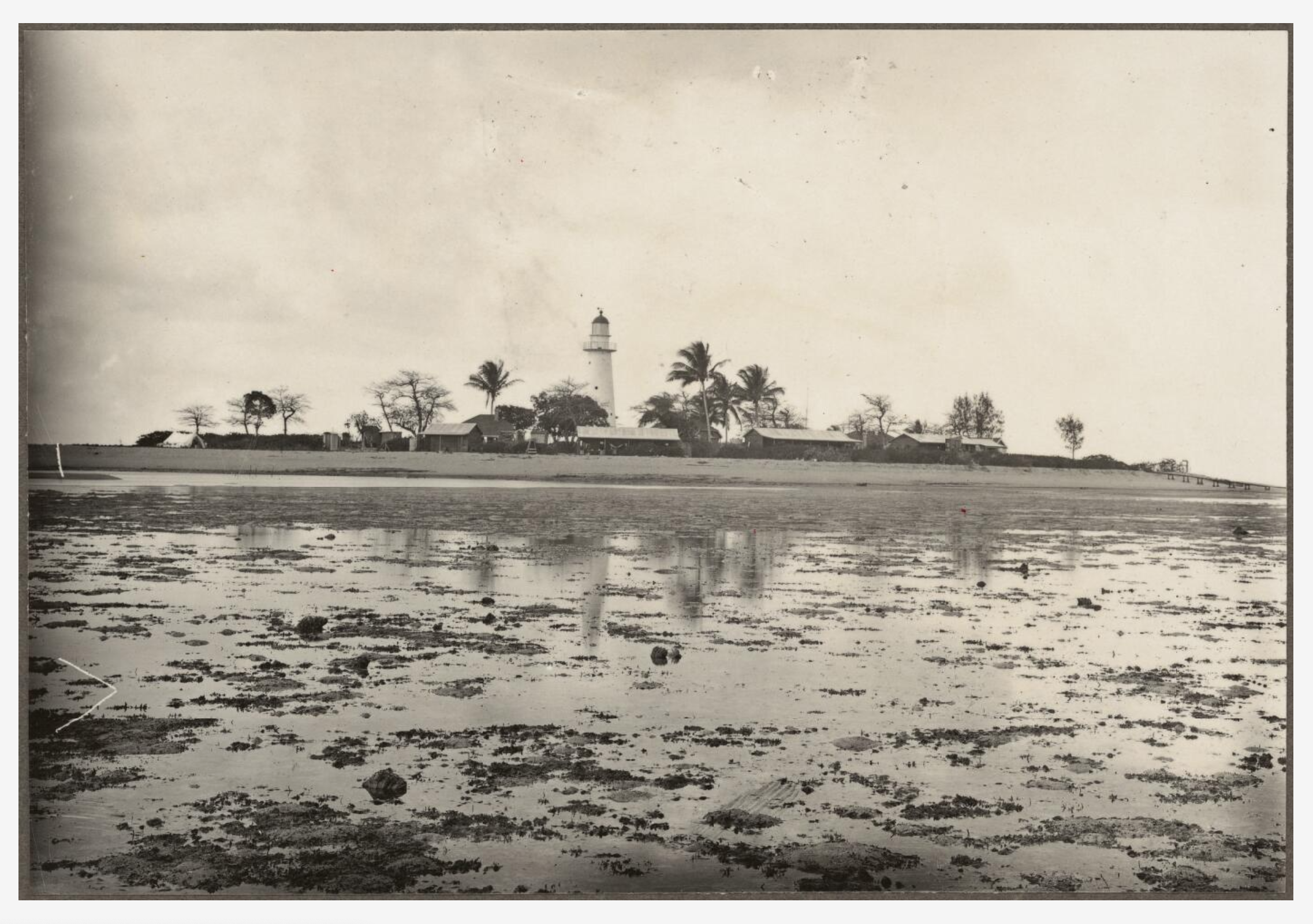

(1928). Low Isle viewed from the south west across the lagoon at low tide, Queensland, 1928.

(1928). A panoramic view from the balcony of the lighthouse looking southeast, Low Islands, Queensland, 1928.

Inscription: "To Mrs. C. M. Yonge, in accordance with my promise, & in remembrance of the Australian Museum party's stay with the British Great Barrier Reef Expedition on Low Isles, North Queensland in October & November, 1928. F.A. Mcneill 12 Feb, 1929"--In ink inside front album cover.

Presentation album to Mattie Yonge by the Australian Museum team who joined the Great Barrier Reef Expedition, Low Islands, Queensland, 1928

(1928). Mort, Iredale and Livingstone at the Australian Museum encampment on the western end of the island, Low Islands, Queensland, 1928.

Five leather bound albums containing some 528 photos are preserved at the National Library of Australia, comprising Sir Charles Maurice Yonge's personal photographic record of the Great Barrier Reef Expedition of 1928-1929, when he was appointed leader at the age of 28 years.

The expedition consisted of twelve scientists, including his new wife Mattie, as medical officer, arriving at Low Isles on 16 July 1928 to begin thirteen months of research.

Pioneering research was undertaken on the relationship between corals and giant clams.

The collection contains images of Port Douglas, Cairns, Kuranda, Daintree, Magnetic Island, flora and fauna, Canberra, Sydney, Thursday Island and nearby islands, the Low Islands, corals, Oceania and the United States of America. The Mattie Yonge album is a presentation album commemorating the Australian Museum team's participation in the expedition.

The success of the 1928 Expedition firmly established Sir Maurice’s international reputation as a zoologist, and in 1932 he was appointed as the first Professor of Zoology at the University of Bristol.

His achievements over the course of a long professional career earned him many accolades, including election as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1946, the award of a CBE in 1954, the conferment of a knighthood in 1967, and of honorary degrees from four universities.

His personal life was touched by tragedy when his wife Mattie died in 1945.

The expedition itself published seven volumes of scientific material in addition to articles in scholarly journals. The Great Barrier Reef Expedition 1928-1929, Yonge, C. M. (Charles Maurice) is available to view at the Douglas Shire Library in Mossman, and also digitally via the link below.

Maurice Yonge also published a book aimed at a general audience – A year on the Great Barrier Reef (1930). The expedition team’s research pioneered studies into coral physiology and continues to be a vital reference material for contemporary study.

““the greatest marine science venture on a global scale since the Challenger oceanographic expedition more than fifty years earlier.””

AFTER 50 YEARS, Sir Maurice returns to Low Isles

Sir Maurice Yonge arrived back in far north Queensland in early 1978, accompanied by his second wife, Lady Phyllis Yonge.

With the assistance of AIMS personnel Martin Jones, Ivan Hauri and others, the Yonges conducted research at various locations in the Palm Islands Group, north of Townsville, including the reef flat between Brisk and Falcon Islands.

During this work, the Yonges were accommodated at Orpheus Island Resort.

The trip included a return visit to Low Isles, where Sir Maurice had led the first research expedition 50 years before.

In a later report to AIMS, he noted his disappointment in the state of the reef at Low Isles.

“I had the opportunity of revisiting Low Isles, off Port Douglas and the scene of the expedition I led 50 years ago and which worked there for 13 months. It was sad to find the reef surface, then the site of the richest possible array of living organisms and a natural experimental aquarium, now almost entirely dead. This appears to be the effect of sediment brought down by the Daintree River following the clearance of rain forest.”

We extend our appreciation to James Cook University for this information supplied.

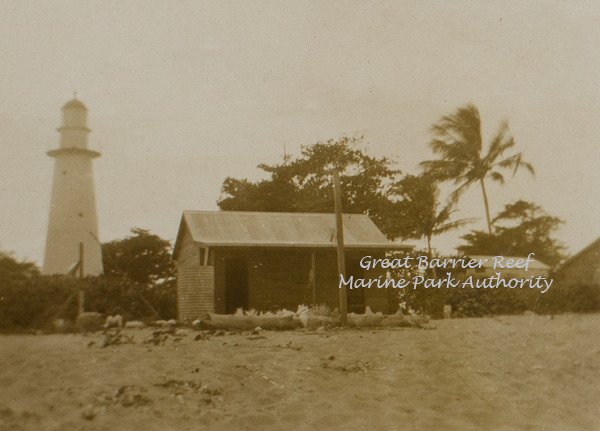

Sir C.M. Yonge (1928). Historical photograph taken at Low Isles during the 1928-1929 Great Barrier Reef Expedition, led by Sir Charles Maurice Yonge.

Sir C.M. Yonge (1928). Historical photograph taken at Low Isles during the 1928-1929 Great Barrier Reef Expedition, led by Sir Charles Maurice Yonge.

Sir C.M. Yonge (1928). Historical photograph taken at Low Isles during the 1928-1929 Great Barrier Reef Expedition, led by Sir Charles Maurice Yonge.

A BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF EXPEDITION 1928-1929

Compiled by Frank Carter

On Trinity Sunday, the 10th of June 1770, Captain Cook had logged a "small island which lay about 2 leagues from the main" at Latitude 16° 20' South.

The first to study the Reef was Professor Beete Jukes who came in 1842 on the survey vessel H.M.S. Fly.

The Great Barrier Reef Committee was formed in Brisbane in 1922. Its function was to investigate the origin, growth, and natural resources of the Great Barrier Reef. In 1926 the Committee had organised a three months stay for a small party on Michaelmas Cay. A bore was sunk to 600 feet to ascertain the nature of the foundations of the reef.

In 1926 on his return to England, Sir Matthew Nathan was requested to interest British scientists in an expedition to the reef. His efforts were successful. The money raised enabled the Expedition to depart on the liner Ormonde, arriving in Brisbane on the 9th of July 1928.

On this island, Low Isles, the nine men and six women of the Biological Section would live and work for a year. The three men of the Geological Section made an extensive cruise of the Reef on the M.L. Tivoli, from Townsville to Flinders Island and back to Mackay, calling at Low Isles each way.

The Expedition left Brisbane by train on the 11th of July 1928, a two-and-a-half day trip to Cairns (the population was then 7000), staying a few days. On the 16th of July they travelled to Low Isles on the M.L. Daintree. This vessel supplied the settlement on the Daintree River and with the Echo, also supplied the lighthouse.

The area of the island was then about three acres, but erosion over the years has appeared to have affected that area of the beach where the Expedition huts were erected (it is now about 1 acre).

The huts had been erected at the direction of the Committee by J.E. Young, a Queensland naturalist. The huts comprised a laboratory 35 feet x 18 feet and a dining room. A large living but with a store and dark room, another similar living hut, a small bathroom with toilets, lastly a hut for Aborigines.

The launch used by the Expedition was the Luana, a 39 foot ketch-rigged yacht with a 26 H.P. engine. Built for pleasure cruising in Moreton Bay, it was sailed north by the owner Mr. A.C. Wishart, mate Mr. Vidgen, loaned for the duration of the expedition with the services of the owner as skipper. This craft was last seen by the writer in Brisbane in 1943, then believed to be owned by Mr. Manahan, chain store operator.

A 20-foot whaleboat, Dancing Wave, was purchased. Maintenance of hull and motor was a problem. A dinghy with outboard was obtained and with the Luana, served their purpose. Larger vessels as the M.L. Daintree were used for longer journeys. Lizard Island, Howick Isles, Three Isles, the reef as far out as Ruby and Escape, Pixie Reef and Michaelmas Cay were visited.Low Island yielded only poor results of specimens with dredge and trawl. Lizard proved a very good area.

Some instruments used were: thermograph, hydrograph with wet and dry bulb, maximum and minimum thermometer in a tropical meteorological hut [Stevenson screen], and barograph in the lighthouse; a sunshine recorder, anemometer and an automatic tide gauge; a Secchi Disc for lowering into the water for clarity tests and a water bottle for temperature testing attached to a line running over a meter wheel to measure depth. A tow net and type of dredge and an Agassi’s trawl were part of the equipment.

During the Expedition's stay on Low Isles there were many visitors from the Australian Museum and Universities.

Two items worth mentioning, firstly the Expedition considered Pixie Reef was a young reef; in November 1928 it had a shingle cay about 50 yards in circumference. In 1929, they found two smaller cays about 70 yards apart. At the time of writing there was no cay at all (about 1945).

Secondly, a Royal Australian Air Force flying boat, having taken aerial photographs, landed at Low Isles, and taxied onto the beach. The plane was responsible for the mosaic photographs of Low Isles and other valuable work.

On the 24th of April 1929 four Expedition members sailed from Cairns on the S.S. Taiping to spend some months around Thursday Island and Torres Strait islands. The Expedition left Low Isles on the 28th of July in that year, some members visiting Gladstone. Arrangements made enabled them to take the M.L. Athlone to the Capricorn Group, visiting Heron Island where at the time there was a small turtle cannery. Visiting North Reef they saw the S.S. Cooma, which had run aground on the 7th of July 1926 en-route from Brisbane to Cairns.

The party returned to the mainland via Heron Island. Their stay of one year and twenty days was over.

The information has come from the writer's own experience, photos and details related by his parents, lightkeepers on Low Isles at the time. Further details from A Year on the Great Barrier Reef by the Expedition leader Dr. C.M. Yonge

Throughout Sir Maurice’s life, he built an extensive private collection of books, reports and papers relating to the ocean and its life. In 1982 he sold his private scientific library to the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).

Made up of several thousand works published from the early 1700s to the twentieth century. subjects include oceanography, malacology, fisheries, marine biology, marine botany and zoology, biographies, along with records of major scientific expeditions, history, marine fiction, anthologies and poetry, and even cookbooks.

The collection held pride of place in the AIMS Library from 1982 to 2016 and was gifted to James Cook University Library in 2016 in order to ensure its preservation, and is now housed under strict archival conditions in Special Collections.

In late March 2022, LIPS received a newly published paper about the 1928-29 Great Barrier Reef Expedition, led by Tom Spencer and Barbara Brown in the UK: ‘A close and friendly alliance: Biology, Geology and the Great Barrier Reef Expedition of 1928-1929’.

Both Tom and Barbara have spent countless hours wading through archival records at London’s Royal Society, Royal Geographical Society and The Natural History Museum. This is a treasure trove of information about how the Expedition was organised, the science that was carried out and the ongoing legacy that the work of the Expedition continues to have in global coral reef science. We trust that our readers enjoy this interesting and informative review of an important part of the history of Australian coral reef science.

Abstract

The 1928–1929 Great Barrier Reef Expedition marks an important milestone in the evolution of modern coral reef science, from its nineteenth-century theoretical and deductive foundation – so clearly exemplified in Darwin’s coral reef theory – to the twentieth-century focus on empirical and analytical studies.

Here, we consider the anatomy of the expedition, its antecedents, its immediate scientific achievements and its longer-term legacy. This truly interdisciplinary expedition differed from its ship-borne or short-stay reef reconnaissance predecessors, being housed on a single reef and sand cay (Low Isles, northern Great Barrier Reef) for a period of 13 months. Its intensive, rather than extensive, investigations involved meticulous microscopic work and pains taking laboratory and field observation, measurement and experimentation, cataloguing linkages between reef habitats, tidal processes and physical and chemical properties of water, as well as a quantitative inventory of reef-flat and reef-front biota spatially grounded in accurate transect surveys and planimetric controls. Results were published in the Expedition’s exhaustive Scientific Reports over the next three decades, as well as in a host of other scientific journals.

We assess the Expedition’s major achievements: highlighting the importance of the carnivorous diet of corals; describing a natural coral bleaching event and mechanisms of algal loss; determining how corals survive submerged within variably oxygenated and turbid waters; estimating adult and juvenile coral growth rates and the effects of transplanting corals; understanding relationships between lunar periodicity and mass spawning of corals; and recognizing the commonalities and differences in reeftop sediments and landforms and their indicative role of past storms and sea levels and contemporary morpho-dynamic changes. Finally, we argue that these and many other topics explored during the expedition continue to be relevant in modern reef science, not least in providing an exceptional set of ecological and geomorphological benchmarks against which it has been possible both to measure one hundred years of ecological and morphological change and to provide a dynamical environmental envelope against which to assess potential future changes.

Extract from

A playground for science: Great Barrier Reef

by Celmara Pocock

The highpoint of scientific research in the early twentieth century was the British Expedition of 1928-29 to Low Isles. The Expedition was reported internationally and created great excitement in Australia and Britain. The Melbourne Argus reported on 13 December 1927 that ‘The expedition had aroused more interest than any other topic at meetings of scientific societies in Britain’.

The expedition comprised a team of talented young scientists led by Charles Yonge. Ten people, including three women (Anne Stephenson, Gweneth Russell and Martha Yonge) left London in May 1928. Dr Martha Yonge, the ‘charming young wife’ of Maurice Yonge, served as medical officer to the expedition. They were later joined by Sidnie Manton, zoologist, and Elizabeth Fraser, Senior Lecturer in Zoology, University of London. After leaving London in May 1928, they arrived in Brisbane in July and then travelled for two and a half days by rail to Cairns; and a further five hours to reach the Low Isles by launch. At the height of activity there were twenty-three scientists on Low Isles including five scientists from the Australian Museum and additional British scientists who joined the party for shorter periods. Several Aboriginal labourers from Yarrabah and a cook and domestic servant provided additional support to the expedition.

The core group remained on the island for a year immersed in the wonders of the Reef. The scientists came to know the environments through all seasons and transformed these small coral cays into meaningful landscapes. Yonge later observed,

..the little sand cay on which we lived and which we grew to know so intimately – every tree and every bush; I would say, every grain of sand – during the year that followed...

Carefully planned, the expedition included the construction of the first purpose-built research facilities on the Reef. The scientists thus wrought changes to the physical landscape. Nevertheless, the facilities were rudimentary. Separate sleeping quarters were available for men and women, but some, including those from the Australian Museum, camped in tents. Exposed to the elements and working in open laboratories the environment had a reciprocal impact on the biologists.

As men of flesh and blood they sank slowly into a sort of melting decay under the savage heat of a humid summer. About 9 o’clock in the morning one begins to feel on Low Island as though one’s spine is being slowly boiled away.

And their work was sometimes destroyed or interrupted by insects, as reported in the Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November 1928,

when somebody did at last manage to develop some photographic plates, an operation the heat makes almost impossible, and put them up to dry, the ants came and chewed off the emulsion.

Despite many discomforts Yonge recalled that ‘the genuine thrill of investigating and living amongst animals of which we had read so much but had never expected to see’ kept scientists enthralled and motivated. According to the Sydney Morning Herald,

Twenty scientists are living on that island for a year. It is not a rest cure by any means. But there are such a lot of delightful things to be collected in the place that they put up with the inconvenience.

Yonge wrote in 1930,

Each pool has an exquisitely beautiful population of tiny coral fish, which for their adequate description need the knowledge of an ichthyologist, the imagery of a poet and the brush of an artist...

The scientific discoveries of the British Expedition were well publicised. One of the first visitors to the Low Isles was journalist Charles Barrett whose newspaper articles were later published as a book. Other scientists from the expedition, including TC Roughley and C. Yonge, also published popular scientific accounts of the Reef.